Sapling

Introduction

The majority of public blockchains allow anyone with access to the Internet to monitor all operations on the chain.

Moreover, by knowing a user’s address (from a payment, for example), anyone can:

read the balance of his account

see incoming and outgoing transactions since the account creation, as well as the amounts sent and recipients.

These aspects may be with the protection of users’ privacy¹, as well as the right to be forgotten².

To remedy this situation, Tezos offers contracts based on the Sapling protocol. This protocol provides both the protection of users’ privacy and transparency with regard to the regulators.

1: On this subject, in the European Union, the regulates the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and the free circulation of such data.

2: The right to be forgotten allows an individual to request the removal of information about them and that may harm them.

Definition of the main concepts

Shielded transaction: A transaction is said to be shielded when an external observer cannot find out any data from it (including the amount, the recipient, and the sender - In practice, an external observer can see the sender if they call the contract.).

Transparent transaction: A transaction is said to be transparent when it is not shielded.

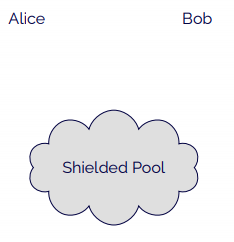

Shielded pool: A shielded pool is a set of tokens whose number can be find out, but whose internal transactions are shielded.

Smart-contract: A smart contract is a computer program whose interactions are described by code and data. It is possible to call a smart contract - its code determines its behavior, depending on the functions called within the contract.

Key management

Sapling is a cryptographic protocol that allows shielded transactions to be conducted, while ensuring that trusted third parties can view the transactions. Three elements need to be identified for this to happen:

The expense key, which should be kept secret and is used to sign transfers.

The viewing key, which is derived from the expense key and allows transactions issued or received to be viewed (it is possible to create viewing keys that allow only transactions issued or transactions received to be viewed).

Addresses that are used to receive transactions are all derived from the expense key. We can derive as many addresses as we want, so, two different users will not be able to know whether or not they are making a transfer to the same person.

Sapling is a cryptographic protocol that uses elliptic curves (Bls 12-381 and jubjub).

Demonstration

Example without monitoring of the transaction by a third party

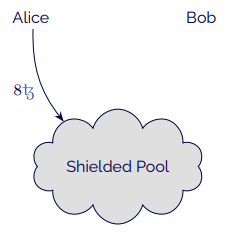

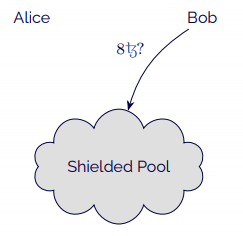

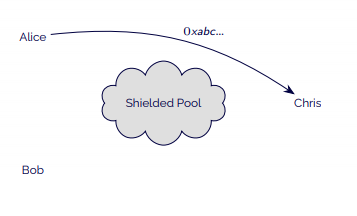

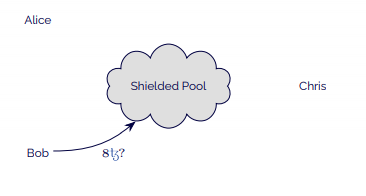

In this example, Alice wants to send 8 tez to Bob, without anyone else knowing.

- Alice begins by creating tokens in the shielded pool, sending 8 to the contract.

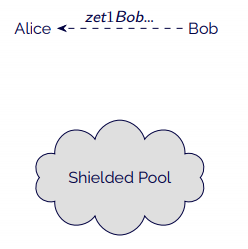

- Bob derives an address from his view key and sends it to Alice.

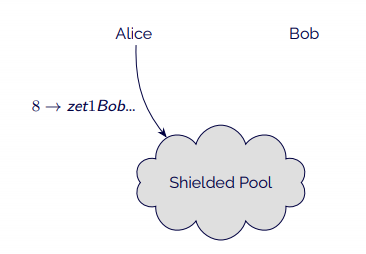

- Alice sends Bob the tokens through the shielded pool.

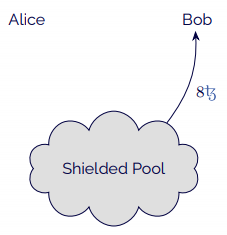

- Bob can then claim the tokens that he has received.

- The contract itself then sends 8 tez and withdraws the corresponding tokens from the shielded pool.

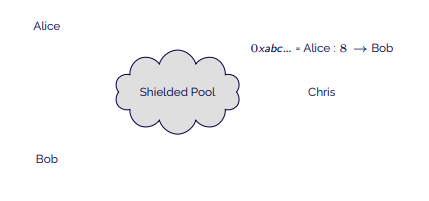

In this scenario, someone could notice that Alice is sending 8 tez and that Bob is also withdrawing 8 tez. This might make it possible to guess that there has been a transaction between the two, especially if the deposit and the withdrawal are temporally close.

Ideally, Bob should not withdraw his tokens and should use them to pay transactions.

To increase his anonymity, Bob can ensure that he never interacts with the contract to deposit or withdraw tez. This example is a simple case of the use of Sapling.

It is also possible to allow a third party, a regulator for example, to control all transactions of the Sapling contract. Example with monitoring of the transaction by a third party

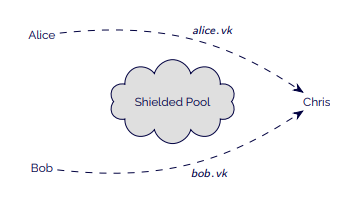

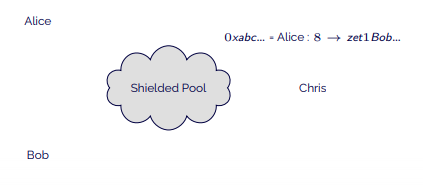

In this scenario, only Chris’ address can send transactions (apart from deposits and withdrawals) to the shielded pool:

- Alice and Bob identify themselves to Chris and send him their respective viewing keys. (This may have been done before the current transaction.)

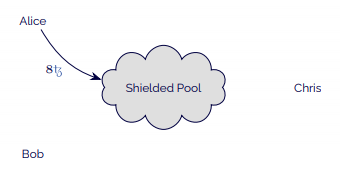

- Alice creates tokens in the shielded pool, sending 8 tez to the contract.

- Bob derives an address from his viewing key and sends it to Alice (Alice could also address it to Chris because he has access to Bob’s key and so may also be able to derive an address from it.).

- Alice creates a transaction of 8 tez to Bob and sends it to Chris.

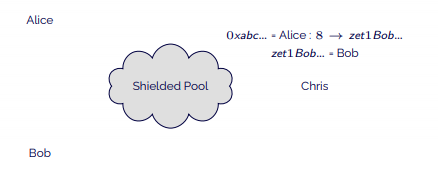

- Chris notes, from Alice’s keys, that it relates to a transaction coming from Alice to an address.

- Chris can then verify, using Bob’s key, that this address is derived from Bob’s key.

- Both keys show Chris the amount. He then knows that it relates to a transaction of 8 tokens from Alice to Bob.

- He decides that this transaction is lawful and sends the transaction to the contract.

- Bob can then claim the tokens that he has received and receive his 8 tez.

This example shows the case where Chris deals with validating the compliance of operations, potentially because he is answerable for what happens in the contract, or even because he is responsible for protecting Alice (and the other members of the contract) against potentially fraudulent transactions. Furthermore, if he decides that an operation is not valid, he may decide to contact Alice to tell her about it and ask her for more information regarding this transaction, or simply to verify that she has not had her wallet stolen and that she is indeed the originator of this transaction.

Chris is not necessarily a human; he may also be a simple secure oracle³ that has viewing keys and automatically conducts transactions where the parties are known.

In both examples, we have assumed that the tokens represented tez. This is not mandatory and we might suppose that the tokens represented any other fungible asset (financial assets, raw materials, etc.). In this case, the regulator could also manage the deposits and withdrawals. There would no longer be any direct interaction between the current asset and its representation on the contract (as we could do with tez). The contract might then have an evidential value in a dispute.

3: An oracle is a program external to the blockchain, generally standalone, the role of which is to make calls to a smart contract to give it orders according to parameters that the smart contract cannot or does not need to control.